|

| Comb jellyfish at the Georgia Aquarium, Atlanta, Georgia, 2 August 2016. |

Showing posts with label digital preservation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label digital preservation. Show all posts

Saturday, August 6, 2016

SAA day two: electronic records

Labels:

digital preservation,

e-records,

federal records,

SAA 2016

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

Best Practices Exchange: day three

|

| Memorial Hall, Pennsylvania State Museum, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 21 October 2015. |

This year's BPE sessions took place in the Pennsylvania State Museum building, and attendees repeatedly passed through the Museum's Memorial Hall, which is dedicated to the vision of Pennsylvania founder William Penn as they made their way from one session to the next. Memorial Hall features a mammoth, strikingly modernist sculpture of Penn, a reproduction of Pennsylvania's original colonial charter, and a mural by Vincent Maragliotti depicting the state's history from the colonial era to the mid-1960s.

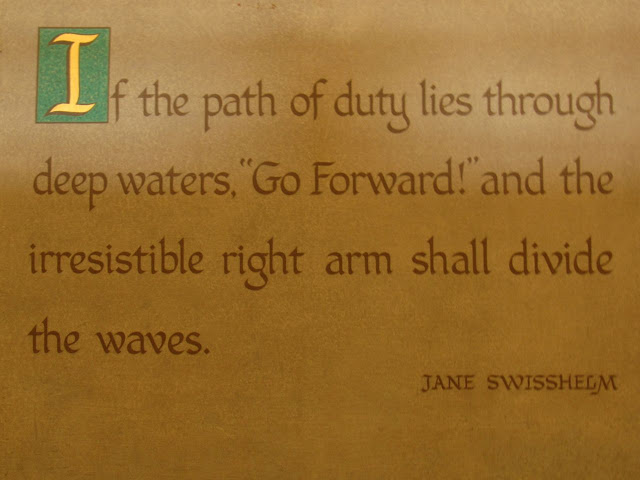

Painted beneath the mural are quotations from over a dozen prominent Pennsylvanians. I scanned them this morning as I was heading to a session, and several of them seemed strikingly resonant.

The BPE exists because archivists, librarians, and other people recognize that the processes and policies that worked so well in an analog world don't work so well in the digital era. This year, many presenters detailed how they're developing and documenting new processing workflows and drafting new preservation and records management policies. We're creating these things not because we wish to sow discord or promote ourselves but because our mission -- preserving and providing state government and other born-digital content -- demands it of us.

BPE attendees have always stressed that failure can be just as instructive as success, and Kate Theimer stressed in her plenary address that we need to create organizational cultures in which failure is recognized as part and parcel of innovation. I would argue that demonstrating a certain degree of compassion is part and parcel of this effort. Most of the people who self-select to become archivists and librarians were conscientious students who took pride in having the "right" answer, and we have to keep gently reminding our perfectionist peers that failure itself is neither unusual nor a sign of incompetence. Failure to learn from a failure is far more damaging.

I don't know whether the "irresistible right arm shall divide the waves," but as Pennsylvania State University records manager Jackie Esposito emphasized in this morning's plenary address, those of us who are actively grappling with digital preservation and electronic records management are doing so in part because the risks associated with not doing so -- financial losses, legal sanctions, tarnished institutional reputations, inability to conduct business -- are even greater than the risks associated with wading into the deep waters of digital preservation and electronic records management. We don't have any choice but to keep going forward, even if the only right -- or left -- arms pushing against the waves are our own.

Monday, October 19, 2015

Best Practices Exchange 2015: day one

|

| Light fixture, Pennsylvania State Museum, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 19 October 2015. |

I'm a little under the weather and am still thinking through some of the things I heard about today, so this post is going to be brief. However, I did want to pass on something that really piqued my interest:

- A group of Michigan archivists and librarians doing hands-on digital preservation work have formed a grassroots organization, Mid-Michigan Digital Practitioners, that meets twice a year to exchange information. The group has no institutional sponsor, has no formal leadership structure, and charges no membership dues; however, the website of Michigan State University's Archives and Historical Collections includes information about and presentations delivered at past meetings. Mid-Michigan Digital Practitioners has capped its size in an effort to ensure that it remains small enough to allow members to form a tightly knit, geographically concentrated community of practice, and I think that this is a good thing. Local and regional professional organizations and regional, national, and international communities of practice are all incredibly valuable, but local, less formalized communities can propel enduring collaboration and can be far less intimidating to people who are just beginning to grapple with digital preservation issues. I would love to see lots of little, unstructured, and locally based digital preservation groups pop up all over the place.

- The technologies we will use to manage and preserve archival records are the same technologies we will use to preserve records that are not permanent but which have lengthy retention periods. When making the case for digital preservation to CIOs and other high-ranking, we should consider focusing less on the former and emphasizing that we can help care for the latter. If we create an environment in which people are comfortable sending records that have long retention periods to an archives-governed storage facility -- just as they are currently comfortable sending paper records that have long retention periods to a different archives-operated storage facility -- we can easily take care of preserving those records that warrant permanent preservation.

- All too often, we think in terms of what records creators must do in order to comply with regulations, laws, or records management best practices. We should instead assess the environment in which records creators operate, identify the problems with which creators are struggling, and then stress how we can help to solve these problems.

- When we talk about "electronic records," many people simply assume that we're advocating scanning paper documents and then getting rid of all paper records. We need to make sure that people understand that we're focusing on those materials that are created digitally and will be managed and preserved in digital format. How do we do this?

Thursday, January 8, 2015

Jump In: electronic records

Do you lack hands-on electronic records experience? Are you growing more and more concerned about the floppy disks, CD's, and other portable media lurking in your paper records? Do you work best when you have a firm deadline? Do you like winning prizes?

If you answered "yes" to most or all of the above questions, you need to know that the Manuscript Repositories Section of the Society of American Archivists (SAA) is sponsoring its third Jump In initiative, which supports archivists taking those essential first steps with electronic records. Using OCLC Research's excellent You’ve Got to Walk Before You Can Run: First Steps for Managing Born-Digital Content Received on Physical Media as a guide, Jump In participants will inventory some or all of their physical media holdings and write a brief report outlining their findings and, possibly, next steps.

Jump In participants will be granted access to a dedicated listserv, and every participant will be entered into a raffle to win a free seat ($185 value) in any one-day Digital Archives Specialist workshop offered by SAA. In addition, select participants will be invited to present their findings at the Section's 2015 annual meeting in Cleveland.

The deadline for committing to Jump In is 16 January 2015, and the deadline for submitting reports is 1 May. For more information about the survey process, possible report topics, and rules of participation, consult the Jump In 3: Third Time's a Charm announcement.

This is a great way to start taking some electronic records baby steps; even if you're a lone arranger, you should be able to craft a survey project that can easily be completed by 1 May. Kudos to the Manuscripts Repositories Section for creating and sustaining this initiative.

If you answered "yes" to most or all of the above questions, you need to know that the Manuscript Repositories Section of the Society of American Archivists (SAA) is sponsoring its third Jump In initiative, which supports archivists taking those essential first steps with electronic records. Using OCLC Research's excellent You’ve Got to Walk Before You Can Run: First Steps for Managing Born-Digital Content Received on Physical Media as a guide, Jump In participants will inventory some or all of their physical media holdings and write a brief report outlining their findings and, possibly, next steps.

Jump In participants will be granted access to a dedicated listserv, and every participant will be entered into a raffle to win a free seat ($185 value) in any one-day Digital Archives Specialist workshop offered by SAA. In addition, select participants will be invited to present their findings at the Section's 2015 annual meeting in Cleveland.

The deadline for committing to Jump In is 16 January 2015, and the deadline for submitting reports is 1 May. For more information about the survey process, possible report topics, and rules of participation, consult the Jump In 3: Third Time's a Charm announcement.

This is a great way to start taking some electronic records baby steps; even if you're a lone arranger, you should be able to craft a survey project that can easily be completed by 1 May. Kudos to the Manuscripts Repositories Section for creating and sustaining this initiative.

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

CoSA SERI PERTTS Portal

If you know what the above means, feel free to skip this post. If you don't, here's an explanation:

- "CoSA" is the Council of State Archivists.

- "SERI" is CoSA's State Electronic Records Initiative, which seeks to improve the management of state government electronic records and is funded by the Institute for Museum and Library Services and the National Historic Records and Publications Commission.

- "PERTTS" refers to -- look at the image.

- "Portal" refers to a new, Web-based collection of resources that will be of interest not only to state government archivists and records managers but also to other archivists who work with electronic records.

- Information about CoSA's electronic records webinars, including a schedule of upcoming sessions and links to recordings and slides from past webinars.

- Handouts and slides prepared by instructors of the July 2013 SERI Introductory Electronic Records Institute: Mike Wash (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration), Doug Robinson (National Association of State Chief Information Officers), Pat Franks (San Jose State University), and Cal Lee (University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill).

- How-to guides and short videos that explain how to complete various processes or use specific tools. Areas covered: file authentication and integrity processes, detection of duplicate files, file format conversions, identifying file properties, renaming files, and ingest/accessioning processes.

- Links to electronic records training opportunities offered by other organizations.

- Information about the State Electronic Records Program Framework, which is based upon the Digital Preservation Capability Maturity Model and enables state archives (and anyone else interested in doing so) to assess their preservation infrastructure and identify areas for improvement. If you're employed by a state archives and took the SERI self-assessment, you'll be particularly interested in the portal's discussion of the tangible steps needed to advance from Level 0 to Level 4 within each of the framework's 15 components and in its practical tips for completing the self-assessment the next time it's offered.

- An ever-expanding and keyword searchable database of summary information about and links to resources relating to virtually every aspect of electronic records management and preservation. If you create a free PERTTS portal account, you'll be able to comment upon these resources; if you would prefer not to create an account, you'll still be able to access them. CoSA will also develop a simple form that will enable you to suggest resources that should be added to the portal.

- An electronic records glossary that draws from a wide array of sources.

- Brief case studies and examples of real-world implementations of metadata standards, security protocols, Archival Information Package construction, and other facets of electronic records work.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Best Practices Exchange 2013: digital imaging, data management, and innovation

The 2013 Best Practices Exchange (BPE) ended last Friday, and I wrote this entry as I was flying from Salt Lake City to Ohio, where I spent a few days tending to some family matters. I've been back in Albany for about 46 hours, but I haven't had the presence of mind needed to move this post off my iPad until just now.

I'm leaving this BPE as I've left past BPE's: excited about the prospect of getting back to work yet so tired that I feel as if I'm surrounded by some sort of distortion field.

The last BPE session featured presentations given by Jason Pierson of FamilySearch and Joshua Harman of Ancestry.com, and I just want to pass along a few interesting tidbits and observations:

I'm leaving this BPE as I've left past BPE's: excited about the prospect of getting back to work yet so tired that I feel as if I'm surrounded by some sort of distortion field.

The last BPE session featured presentations given by Jason Pierson of FamilySearch and Joshua Harman of Ancestry.com, and I just want to pass along a few interesting tidbits and observations:

- Both firms view themselves as technology companies that focus on genealogy, not genealogy companies that make intensive use of technology. They work closely with archives and libraries, but their overall mission and orientation are profoundly different from those of cultural heritage institutions. And that's okay.

- Both firms have opted to encode the preservation masters of their digital surrogates in JPEG2000 format instead of the more popular TIFF format. They've discovered that, if necessary, they can create good TIFF images from JPEG2000 files and that JPEG2000 files are more resistant to bit rot than TIFF files. The loss of a single bit can make a TIFF file completely unrenderable, but JPEG2000 files may be fully renderable even if they're missing several bits. However, the relative robustness of JPEG2000 files can also be problematic: JPEG2000 files that are so badly corrupted that only blurs of color will be displayed may remain technically renderable (i.e., software that can read JPEG2000 files may open and display such files without notifying users that the files are corrupt. One firm discovered well after the fact that it had created tens thousands of completely unusable yet ostensibly readable JPEG2000 files.

- Ancestry has developed some really neat algorithms that automatically adjust the contrast on sections of an image. Most contrast corrections lighten or darken entire images, but Ancestry's tool adjusts the contrast only on those sections of an image that are hard to read because they are either too light or too dark. Ancestry has also developed algorithms that automatically enhance images and facilitate optical character recognition (OCR) scanning of image files. As you might imagine, attendees were really interested in making use of these algorithms, and Harmon and other Ancestry staffers present indicated that the company would be willing to share them provided that doing so wouldn't violate any patents. (I share this interest, but I think that archives owe it to researchers to document the use of such tools. Failure to do so can leave the impression that the original document or microfilm image is in much better shape than it is and cause researchers to suspect that the digital surrogate has also been subjected to other, more sinister manipulations.)

- FamilySearch and Ancestry may well have the largest corporate data troves in the world. FamilySearch is scanning vast quantities of microfilm and paper documents and generates approximately 40 terabytes (yes, terabytes) of data per day. They're currently using Tessella's Safety Deposit Box to process the files and a mammoth tape library to store all this data. At present, they're trying to determine whether Amazon Glacier is an appropriate storage option; if Glacier doesn't work out, FamilySearch will likely build a mammoth data center somewhere in the Midwest. Ancestry is also scanning mammoth quantities of paper and microfilmed records and currently has approximately 10 petabytes (yes, petabytes) of data in its Utah data center.

- After a lot of struggle, Ancestry learned that open source and commercial software work really well for tasks and processes that aren't domain-specific but not so well for unique, highly specialized functions. For example, Ancestry discovered that none of the available tools could handle a high-volume and geographically dispersed scanning operation involving roughly 1,400 discreet types of paper and microfilmed records, so it devoted substantial time and effort to developing its own workflow management system. Archives and libraries typically don't deal with such vast quantities or such varied originals, and I think it makes sense for cultural heritage professionals to focus on developing digitization workflow best practices and standards that are broadly applicable. However, Ancestry's broader point is well-taken; sometimes, building one's own tools makes more sense than trying to make do with someone else's tools.

- FamilySearch and Ancestry have a lot more freedom to innovate -- and to cope with the accompanying risk of failure -- than state archives and state libraries. Pierson and Harman both emphasized the importance of taking big risks and treating failure as an opportunity to learn and grow, but, as one attendee pointed out, government entities tend to be profoundly risk-averse. In some respects, this is understandable: a private corporation that missteps has to answer only to its investors or shareholders, but a government agency or office that blunders is accountable to the news media and the tax paying public. However, if we sit around on our hands and wait for other people to solve our problems, we'll never get anywhere. I've long been of the opinion that those of us who work in government repositories and who are charged with preserving digital information need to keep reminding our colleagues and our managers that as far as digital preservation is concerned, we really have only two choices: do something and accept that we might fail, or do nothing and accept that we will fail. I'm now even more convinced that we need to keep doing so.

Friday, November 15, 2013

Best Practices Exchange 2013: movies, partnerships, and stories

I wasn't feeling particularly well yesterday, and when I walked into the closing discussion of the 2013 Best Practices Exchange (BPE), I found myself thinking I would have a really hard time explaining to my colleagues what I learned at this year's BPE; I loved every session I attended, but I didn't believe that I could pull together any coherent thoughts about them. Fortunately, Patricia Smith-Mansfield (State Archivist of Utah) and Ray Matthews (Utah State Library) were fantastic discussion moderators, and the questions they asked and the insights offered by several other BPE attendees really helped me to make sense of yesterday's events. Thanks, guys!

Yesterday, Milt Shefter of the Science and Technology Council of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences delivered an excellent lunchtime presentation that focused upon the Academy's efforts to address the digital preservation issues facing the motion picture industry and individual filmmakers. Filmmaking is becoming a digital enterprise, and filmmakers and production companies are facing a host of new challenges: file formats change so quickly that films produced as recently as five years ago may no longer be renderable, video files require vast quantities of storage space, there are no widely accepted preservation standards, and the need to migrate to newer storage media every five to ten years poses a particular risk to files that may be viewed more as products than as works of art.

Shefter asserted that the industry and filmmakers are keenly aware of the need for open, widely accepted standards and a storage medium robust and durable enough to withstand some benign neglect but lack the clout needed to push hardware and software manufacturers in this direction. Even in my stupor, I was struck by this assertion. The motion picture industry is a multi-billion dollar enterprise; surely it has more clout than the archival and library communities! However, I didn't put two and two together until someone pointed out this morning that perhaps the Academy and the cultural heritage community should consider establishing a formal partnership around storage, format, and preservation issues. This isn't exactly a new idea -- the Library of Congress's National Digital Information Infrastructure Preservation Program brought together archives, libraries, the motion picture industry, the recording industry, the video game industry, and others seeking to preserve digital content -- but it's one that merits further exploration.

Immediately after Shefter's speech ended, Sundance Institute Archives Coordinator Andrew Rabkin introduced a screening of These Amazing Shadows, a documentary that traces the development of the (U.S.) National Film Registry, a Library of Congress-led initiative to identify and preserve motion pictures of cultural, historical, or aesthetic significance. Both Rabkin and the film itself stressed that motion pictures insinuate themselves into our collective consciousness because they tell emotionally compelling stories in visually arresting ways, and during this morning's closing discussion one attendee stated that the film left her convinced that we as a community need to identify compelling stories about the importance of digital preservation and to tell them in a vivid, attention-grabbing manner.

I couldn't agree more. All too often, people (a few archivists among them) think that electronic files lack the gripping content and emotional intensity found in paper records and personal papers. However, electronic records and personal files can be as compelling as any paper document. We're talking not only about spreadsheets and databases -- both of which can be deeply compelling to someone who has a certain type of information need -- but also about photographs of babies and the remains of the World Trade Center site, videos documenting weddings and natural disasters, audio files capturing the oral histories of relatives who have since died and musical performances of world-class symphonies, geospatial data documenting real property boundaries and the location of hazardous waste sites, e-mail messages containing professions of love and evidence of criminal activity, and a whole bunch of other immensely valuable, emotionally resonant, practically useful things. Most people know this on some level, but they don't fully realize just how fragile these files are or how devastating their loss would be.

Several documentary filmmakers are currently working on films that focus on digital preservation initiatives and the loss of important digital content, but we need more effort on this front. I vividly recall seeing the Council on Library and Information Resources' Into the Future: On the Preservation of Information in the Digital Age (1998) on PBS, and this film -- more than any of the readings I did in graduate school -- kept popping into my head as I pondered whether I really wanted to make the jump from descriptive archivist to electronic records archivist. We need gripping, story-driven films that highlight the terrible risks to which digital content is subject and the ways in which we can ensure that important content is preserved. These films must speak not only to archivists and wannabe archivists but to the general public and to elected officials and other key stakeholders. (And Into the Future, which is now available only on VHS tape, needs to be transferred onto DVD or, better yet, placed online.)

Image: Snow on the Wasatch Mountains, as seen from Interstate 15 northbound between Lehi and Sandy, Utah, 14 November 2013.

Yesterday, Milt Shefter of the Science and Technology Council of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences delivered an excellent lunchtime presentation that focused upon the Academy's efforts to address the digital preservation issues facing the motion picture industry and individual filmmakers. Filmmaking is becoming a digital enterprise, and filmmakers and production companies are facing a host of new challenges: file formats change so quickly that films produced as recently as five years ago may no longer be renderable, video files require vast quantities of storage space, there are no widely accepted preservation standards, and the need to migrate to newer storage media every five to ten years poses a particular risk to files that may be viewed more as products than as works of art.

Shefter asserted that the industry and filmmakers are keenly aware of the need for open, widely accepted standards and a storage medium robust and durable enough to withstand some benign neglect but lack the clout needed to push hardware and software manufacturers in this direction. Even in my stupor, I was struck by this assertion. The motion picture industry is a multi-billion dollar enterprise; surely it has more clout than the archival and library communities! However, I didn't put two and two together until someone pointed out this morning that perhaps the Academy and the cultural heritage community should consider establishing a formal partnership around storage, format, and preservation issues. This isn't exactly a new idea -- the Library of Congress's National Digital Information Infrastructure Preservation Program brought together archives, libraries, the motion picture industry, the recording industry, the video game industry, and others seeking to preserve digital content -- but it's one that merits further exploration.

Immediately after Shefter's speech ended, Sundance Institute Archives Coordinator Andrew Rabkin introduced a screening of These Amazing Shadows, a documentary that traces the development of the (U.S.) National Film Registry, a Library of Congress-led initiative to identify and preserve motion pictures of cultural, historical, or aesthetic significance. Both Rabkin and the film itself stressed that motion pictures insinuate themselves into our collective consciousness because they tell emotionally compelling stories in visually arresting ways, and during this morning's closing discussion one attendee stated that the film left her convinced that we as a community need to identify compelling stories about the importance of digital preservation and to tell them in a vivid, attention-grabbing manner.

I couldn't agree more. All too often, people (a few archivists among them) think that electronic files lack the gripping content and emotional intensity found in paper records and personal papers. However, electronic records and personal files can be as compelling as any paper document. We're talking not only about spreadsheets and databases -- both of which can be deeply compelling to someone who has a certain type of information need -- but also about photographs of babies and the remains of the World Trade Center site, videos documenting weddings and natural disasters, audio files capturing the oral histories of relatives who have since died and musical performances of world-class symphonies, geospatial data documenting real property boundaries and the location of hazardous waste sites, e-mail messages containing professions of love and evidence of criminal activity, and a whole bunch of other immensely valuable, emotionally resonant, practically useful things. Most people know this on some level, but they don't fully realize just how fragile these files are or how devastating their loss would be.

Several documentary filmmakers are currently working on films that focus on digital preservation initiatives and the loss of important digital content, but we need more effort on this front. I vividly recall seeing the Council on Library and Information Resources' Into the Future: On the Preservation of Information in the Digital Age (1998) on PBS, and this film -- more than any of the readings I did in graduate school -- kept popping into my head as I pondered whether I really wanted to make the jump from descriptive archivist to electronic records archivist. We need gripping, story-driven films that highlight the terrible risks to which digital content is subject and the ways in which we can ensure that important content is preserved. These films must speak not only to archivists and wannabe archivists but to the general public and to elected officials and other key stakeholders. (And Into the Future, which is now available only on VHS tape, needs to be transferred onto DVD or, better yet, placed online.)

Image: Snow on the Wasatch Mountains, as seen from Interstate 15 northbound between Lehi and Sandy, Utah, 14 November 2013.

Thursday, October 24, 2013

More Podcast, Less Process

Well, this is cool: More Podcast, Less Process is a new podcast that features "archivists, librarians, preservationists, technologists, and information

professionals [speaking] about interesting work and projects within and involving

archives, special collections, and cultural heritage." The first episode, CSI Special Collections: Digital Forensics and Archives, featured Mark Matienzo of Yale University and Donald Mennerich of the New York Public Library and debuted at the start of this month. The second, How to Preserve Change: Activist Archives and & Video Preservation, was released yesterday. In it, Grace Lile and Yvonne Ng of WITNESS discuss the challenges associated with preserving video created by human rights and other activists, producing activist video in ways that support long-term preservation, and WITNESS's impressive new publication, The Activists’ Guide to Archiving Video.

Hosted by Jefferson Bailey (Metropolitan New York Library Council) and Joshua Ranger (AudioVisual Preservation Solutions), More Podcast, Less Process is part of the Metropolitan New York Library Council's Keeping Collections project. Keeping Collections provides a wide array of "free and affordable services to any not-for-profit organization in the metropolitan New York area that collects, maintains, and provides access to archival materials." This podcast greatly extends the project's reach.

Given the mission and interests of its creators, I suspect that quite a few More Podcast, Less Process episodes will focus on the challenges of preserving and providing access to born-digital or digitized resources. I'm waiting with bated breath.

More Podcast, Less Process is available via iTunes, the Internet Archive, Soundcloud, and direct download. There's also a handy RSS feed, so you'll never have to worry about missing an episode. Consult the More Podcast, Less Process webpage for details.

Full disclosure: Keeping Collections is supported in part by the New York State Documentary Heritage Program (DHP), which is overseen by the New York State Archives (i.e., my employer). However, I'm plugging More Podcast, Less Process not because of its DHP connections but because it's a great resource.

Hosted by Jefferson Bailey (Metropolitan New York Library Council) and Joshua Ranger (AudioVisual Preservation Solutions), More Podcast, Less Process is part of the Metropolitan New York Library Council's Keeping Collections project. Keeping Collections provides a wide array of "free and affordable services to any not-for-profit organization in the metropolitan New York area that collects, maintains, and provides access to archival materials." This podcast greatly extends the project's reach.

Given the mission and interests of its creators, I suspect that quite a few More Podcast, Less Process episodes will focus on the challenges of preserving and providing access to born-digital or digitized resources. I'm waiting with bated breath.

More Podcast, Less Process is available via iTunes, the Internet Archive, Soundcloud, and direct download. There's also a handy RSS feed, so you'll never have to worry about missing an episode. Consult the More Podcast, Less Process webpage for details.

Full disclosure: Keeping Collections is supported in part by the New York State Documentary Heritage Program (DHP), which is overseen by the New York State Archives (i.e., my employer). However, I'm plugging More Podcast, Less Process not because of its DHP connections but because it's a great resource.

Sunday, June 23, 2013

New York Archives Conference 2013 recap

Earlier this month, I had the privilege of attending the joint 2013 meeting of the New York Archives Conference and the Archivists Roundtable of Metropolitan New York, which was held at the C.W. Post campus of Long Island University. I was initially scheduled to give one presentation and agreed at the last minute to speak twice, so I didn't get the chance to attend as many sessions or explore the surrounding area as much as I would have liked. However, I did learn a few interesting things:

- I attended the Society of American Archivists' Privacy and Confidentiality Issues in Digital Archives workshop, which was held the day before the conference began, and I'm pleased to report that both the workshop and instructor Heather Briston (University of California, Los Angeles) are fantastic. I've a substantial amount of time working with records that contain information that is restricted in accordance with various state and federal laws, and I still learned quite a bit. If you get the chance to take this workshop, by all means do so.

- Jason Kuscma, the executive director of the Metropolitan New York Library Council, delivered a thought-provoking plenary address, "(Re)Building: Opportunities for Collaboration for New York's Cultural Heritage Institutions," in which he used post-Hurricane Sandy recovery efforts as an entry point for discussing the concept of collaboration. I was particularly struck by his analysis of why collaboration, which involves sharing of risk, is so difficult: it forces us to admit what we don't know, it makes us confront ambiguity and fluidity, it requires discussion and deliberation, it compels us to share information that we may view as proprietary, it has the potential to expose us to even more conflict than we currently experience, and it makes us worry about who's going to get credit for the successes and blame for the failures. I've been involved in a number of collaborative projects over the years, and some of them went belly-up as a result of some or all of the problems that Kucsma identified. The successful ones worked because people were willing get out of what he referred to as "emotional, cultural, and institutional silos," embrace uncertainty, define achievable goals, and entertain the possibility of working with unconventional partners. As Kucsma pointed out, Hurricane Sandy is merely a dramatic example of a problem that's too large and too complex for any one organization to take on by itself. Archivists and librarians face a growing number of such problems, and we need to figure out how to tackle them together.

- Kucsma also highlighted the existence of a recent report that somehow escaped my attention. I2NY: Envisioning an Information Infrastructure for New York State was prepared at the behest of New York's regional library associations, and it assesses the state's current library information landscape, which already features some collaborative initiatives, and outlines how the library associations can move toward building a fully comprehensive, fully collaborative information infrastructure. The report doesn't discuss born-digital archival records, but it does envision the expansion of the collaborative archival digitization efforts led by the regional library associations (which are now exploring how to incorporate digital surrogates or archival materials into the Digital Public Library of America). It calls for creating innovative professional development opportunities.

- I do not envy curators seeking to preserve born-digital works of art. In addition to worrying about all of the hardware and software, data integrity, storage, metadata, information security, and other technical concerns that anyone seeking to preserve digital resources must address, they also have the unenviable task of sussing out the artist's intent and preserving significant properties that may be unique to each viewer/listener or dependent upon external resources. The interactive (and very cool) short film The Wilderness Downtown requires that each viewer enter an address and then pulls data from Google Street View to create visual content. Static and distortions present on an analog recording of an experimental television show may be the result of media degradation . . . or may be the result of the creator's deliberate manipulations.

- Cornell University's Rose Goldsen Archive of New Media Art holds a host of analog video, old CDs and DVDs that require Mac OS 9 or other obsolete software or hardware, and Internet art. At present, the archive maintains an array of older hardware and software and focuses on documenting playback requirements, digitizing analog content, archiving Web sites, and developing emulation software. It's also using National Endowment for the Humanities grant funding to preserve CD-ROM-based works of art. This grant project should allow Cornell to identify how to conduct technical analyses of digital artworks, develop generalizable user profiles for new media art, create a viable data object model and associated PREMIS or RDF metadata profile, and identify a Submission Information Package structure that will support long-term preservation.

- The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is developing a Digital Repository for Museum Collections that currently houses 60 TB of artwork that was originally stored on floppy disks, CDs, and other portable media. Archivematica will supply this repository's core processing services, and a conservation management application will be created to house descriptive information and document software and other dependencies. MoMA is also exploring using emulation to make digital artworks accessible not only to people who visit MoMA's physical exhibit spaces but also to people who access MoMA's website. MoMA is also in the midst of completing a formal study that compares the fidelity of emulation vs. native hardware and software, and I'm really looking forward to seeing the findings arising from this study.

- Documentary filmmaker Jonathan Minard, whose work in progress Archive examines the future of long-term digital storage, the development of the Internet, and Internet preservation efforts, highlighted an essential but frequently overlooked truth: the Internet is a utility, not a library, and its operations are governed chiefly by market considerations. Cultural heritage professionals disregard this truth at their peril. (BTW, part one of Archive, which focuses on the work of the Internet Archive, is available online.)

- The National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA), a Library of Congress-led membership organization of individuals and organizations seeking to preserve digital cultural heritage materials, is developing Levels of Digital Preservation, a simple, tiered set of guidelines that will allow institutions to assess how well they're caring for their digital holdings. It addresses storage and geographical redundancy, file fixity and data integrity, information security, metadata, and file format issues, and the NDSA group developing it would appreciate your feedback.

- If you want a DSpace-powered institutional repository but lack the IT resources needed to maintain your own DSpace installation, you're in luck: DuraSpace, the non-profit organization that guides the development of DSpace and several other digital access and preservation tools, is now offering DSpace Direct, a hosted DSpace service. For approximately $4,000 a year, you can quickly set up your own DSpace institutional repository, select the language customization and other features that meet your needs, and allow DuraSpace to take care of storing and backing up your data (via Amazon Web Services) and upgrading your DSpace software.

Friday, February 22, 2013

San Jose State SLIS colloquia

Every semester, San Jose State University's School of Library and Information Science offers a series of online colloquia that is freely accessible to anyone with an Internet connection and a modest array of hardware and software. Information about the spring 2013 series has apparently been up for a bit, but I've been out of grad school so long that I've lost my once-profound connection to the rhythms of the academic calendar. However, there's nothing like being appointed to a brand-new Staff Development Team to focus one's mind on free continuing education possibilities . . . .

Several of this semester's colloquia will be of interest to electronic records archivists and other information professionals seeking to preserve born-digital content. Three of them will take place next week, and the fourth will occur in April:

Looking Back on the Preserving Virtual Worlds Projects

Henry Lowood, Curator for History of Science & Technology Collections and Film & Media Collections in the Stanford University Libraries

Monday, 25 February 2013, 6:00-7:00 PM PST

This colloquium will be held in SJSU SLIS's Second Life virtual campus. (You will need to establish a Second Life account and learn the basics of finding SLIS's "island" in order to attend.)

Digital Preservation for the Rest of Us: What's in it for Librarians and Library Users

Philip Gust, Stanford University -- Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe (LOCKSS) program

Tuesday, 26 February 2013, 12:00-1:00 PM PST

This colloquium will be held online via Collaborate Web conferencing (set-up info)

The Next Major Challenge in Records Management is Already Here: Social Media

Anil Chawla, Founder & CEO, ArchiveSocial

Tuesday, 26 February 2013, 6:00-7:00 PM PST

This colloquium will be held online via Collaborate Web conferencing (set-up info)

Professional Ethics for Records and Information Professionals

Norman Mooradian, VP of Information and Compliance, CookArthur Inc.

Tuesday, 16 April 2013, 6:00-7:00 PM PST

This colloquium will be held online via Collaborate Web conferencing (set-up info)

If scheduling conflicts keep you from taking part in a colloquium you wish to attend, don't worry: SLIS regularly posts Webcasts of completed colloquia on its website.

Several of this semester's colloquia will be of interest to electronic records archivists and other information professionals seeking to preserve born-digital content. Three of them will take place next week, and the fourth will occur in April:

Looking Back on the Preserving Virtual Worlds Projects

Henry Lowood, Curator for History of Science & Technology Collections and Film & Media Collections in the Stanford University Libraries

Monday, 25 February 2013, 6:00-7:00 PM PST

This colloquium will be held in SJSU SLIS's Second Life virtual campus. (You will need to establish a Second Life account and learn the basics of finding SLIS's "island" in order to attend.)

Digital Preservation for the Rest of Us: What's in it for Librarians and Library Users

Philip Gust, Stanford University -- Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe (LOCKSS) program

Tuesday, 26 February 2013, 12:00-1:00 PM PST

This colloquium will be held online via Collaborate Web conferencing (set-up info)

The Next Major Challenge in Records Management is Already Here: Social Media

Anil Chawla, Founder & CEO, ArchiveSocial

Tuesday, 26 February 2013, 6:00-7:00 PM PST

This colloquium will be held online via Collaborate Web conferencing (set-up info)

Professional Ethics for Records and Information Professionals

Norman Mooradian, VP of Information and Compliance, CookArthur Inc.

Tuesday, 16 April 2013, 6:00-7:00 PM PST

This colloquium will be held online via Collaborate Web conferencing (set-up info)

If scheduling conflicts keep you from taking part in a colloquium you wish to attend, don't worry: SLIS regularly posts Webcasts of completed colloquia on its website.

Friday, December 7, 2012

Best Practices Exchange, day three

- In a digital world, "selection is rocket science." We can't preserve everything, and we have to focus our efforts on saving only those things that are truly worth saving.

- Over the past decade, we've developed a wide array of good digital preservation tools and processes. Now, we have to assemble them in ways that meet our local needs. Wanting one tool to do everything is not realistic.

- Archivists, librarians, curators, and other people who are trying to preserve digital content are running a relay race, and we should focus more on making sure that we're able to keep our digital content intact and accessible until the next generation of tools and processes emerge (or the next generation of cultural heritage professionals takes our place) and less upon the need to preserve our content "until the end of time" or "forever." Thinking of preservation as a ceaseless, ever-present responsibility can induce paralysis. (It's also unrealistic. A few years ago, I was chatting with a wise colleague and for some reason started bemoaning the lack of digital preservation solutions that would, in one fell swoop, enable me to stabilize a given set of records long enough to pass responsibility for their care on to the next generation of archivists. I mentioned that the title of one superb resource -- the Digital Preservation Management: Implementing Short-Term Solutions for Long-Term Problems workshop and tutorial -- highlighted the problem that electronic records archivists faced, and she looked at me, laughed, and said: "Short-term solutions for long-term problems? In other words, digital preservation is just like life. What makes you think it would be otherwise?")

- Our British colleagues are more adept than we are at casting their digital preservation needs in terms of the advantages preservation provides to business. We can learn from them.

- Earlier this week, influential Internet industry experts Mary Meeker and Liang Wu released a report asserting, among other things, that younger people are moving toward an "asset-light lifestyle." They think in terms of services -- online streaming of music and video, online access to publications and other information, Web services that enable sharing of cars and other durable goods -- instead of physical objects that they will purchase and maintain. As yet, we don't know what the implications of this shift will be. Will we move from a culture that views its heritage in thrifty terms or one that views its heritage as an abundance? Will our next big challenge be selection of content, or will it be provision of access to content?

- One of the biggest challenges we face when trying to find the resources needed to preserve digital content is our own unwillingness to ask difficult questions. What are we doing that isn't good for our organization but somehow affirms someone's job? How can we redirect energy and talent? How can we use what we have in better ways?

Thursday, December 6, 2012

Best Practices Exchange, day two

Yesterday was the second day of the 2012 Best Practices Exchange, and the sessions I attended were delightfully heavy on discussion and information sharing. I had some problems accessing the hotel's wifi last night and the BPE is still going on, so I'm going to post a few of yesterday's highlights before turning my attention back to this morning's discussion:

- Arian Ravanbakhsh, whose morning plenary speech focused on the Presidential Memorandum - Managing Government Records and U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) efforts to implement it, made an important point that all too often gets overlooked: even though an ever-increasing percentage of records created government agencies are born-digital, government archivists will continue to accession paper records well into the future. Substantial quantities of paper federal records have extremely long retention periods and won't be transferred to NARA until the mid-21st century, and, judging from the nodding heads in the audience, most state government archivists (l'Archivista included) anticipate that they'll continue to take in paper records for at least several more decades. Sometimes, I forget that we as a profession will have to ensure that at least two future generations of archivists have the knowledge and skills needed to accession, describe, and provide access to paper records. At the moment, finding new archivists who have the requisite interest and ability isn't much of a challenge -- sadly, archival education programs still attract significant numbers of students who don't want to work with electronic records -- but things might be quite different in 2030.

- Butch Lazorchak of the Library of Congress highlighted a forthcoming grant opportunity: the Federal Geographic Data Committee, which is responsible for coordinating geospatial data gathering across the federal government and coordinates with state and local governments to assemble a comprehensive body of geospatial data, plans to offer geospatial archiving business planning grants in fiscal year 2013. The formal announcement should be released within a few weeks.

- Butch also highlighted a couple of tools about which I was aware but haven't really examined closely: the GeoMAPP Geoarchiving Business Planning Toolkit, which can easily be adapted to support business planning for preservation of other types of digital content, the GeoMAPP Geoarchiving Self-Assessment, which lends itself to similar modifications, and the National Digital Stewardship Alliance's Digital Preservation in a Box, a collection of resources that support teaching and self-directed learning about digital preservation.

- This BPE has seen a lot of discussion about the importance and difficulty of cultivating solid relationships with CIOs, and this morning one state archivist made what I think is an essential point: when talking to CIOs, archivists really need to emphasize the value added by records management and digital preservation. As a rule, we simply haven't done so.

- This BPE has also generated a lot of ideas about how to support states that have yet to establish electronic records programs, and in the coming months you'll see the Council of State Archivists' State Electronic Records Initiative start turning these ideas into action. As a particularly lively discussion was unfolding this morning, it struck me that most of the people taking part in established full-fledged programs only after they had completed several successful projects; in fact, intense discussions about the challenges associated with transforming projects into programs took place at several early BPEs. If you don't have any hands-on electronic records experience and are facing resource constraints, it makes sense to identify a pressing but manageable problem, figure out how to solve it, and then move on to a few bigger, more complex projects. After you've accumulated a few successes and learned from a few surprises or failures, you can focus on establishing a full-fledged program.

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

2012 Best Practices Exchange, day one

Today was the first day of the 2012 Best Practices Exchange (BPE), an annual event that brings together archivists, librarians, IT professionals, and other people interested in preserving born-digital state government information. The BPE is my favorite professional event, in no part because it encourages presenters to discuss not only their successes but also the ways in which unexpected developments led them to change direction, the obstacles that proved insurmountable, and the lessons they learned along the way.

As I explained last year, those of us who blog and tweet about the BPE are obliged to use a little tact and discretion when making information about the BPE available online. Moreover, in some instances, what's said is more important than who said it. As a result, I'm going to refrain from tying some of the information that appears in this and subsequent posts re: the BPE to specific attendees.

Doug Robinson, executive director of the National Association of Chief Information Officers (NASCIO) was this morning's plenary speaker, and he made a couple of really interesting points:

- CIOs are juggling a lot of competing priorities. They're concerned about records management and digital preservation, but, as a rule, they're not worried enough to devote substantial attention or resources to improving records management or addressing preservation issues.

- Cloud computing is now the number one concern of state CIOs, and CIOs are starting to think of themselves less as providers of hardware and software than as providers of services. Moreover, the cloud is attractive because it reduces diversity and complexity, which drive up IT costs. Robinson suspects that most states will eventually develop private cloud environments. Moreover, a recent NASCIO survey indicates that 31 percent of states have moved or plan to move digital archives and records management into the cloud.

- CIOs are really struggling with Bring Your Own Devices issues and mobile technology, and the speed with which mobile technology changes is frustrating their efforts to come to grips with the situation. Citizens want to interact with state government via mobile apps, but the demand for app programmers is such that states can't retain employees who can create apps; at present, only one state has app programmers on its permanent payroll.

- Cybersecurity is an increasingly pressing problem. States collect and create a wealth of data about citizens, and criminals (organized and disorganized) and hacktivists are increasingly interested in exploiting it. Spam, phishing, hacking, and network probe attempts are increasingly frequent. Governors don't always grasp the gravity of the threats or the extent to which their own reputations will be damaged if a large-scale breach occurs. Moreover, states aren't looking for ways to redirect existing resources to protecting critical information technology infrastructure or training staff.

- Most states allocate less than two percent of their annual budgets to IT. Most large corporations devote approximately five percent of their annual budgets to IT.

I was really struck by Mary Beth's explanation of the cost savings Oregon achieved by moving to the cloud. In 2007, the Oregon State Archives was able to develop an HP Trim-based electronic records management system for its parent agency, the Office of Secretary of State. It wanted to expand this system, which it maintained in-house, to all state agencies and local governments, but it couldn't find a way to push the cost of doing so below $100 per user per month. However, the State Archives found a data center vendor in a small Oregon town that would host the system at a cost of $37 per user per month. When the total number of users reaches 20,000 users, the cost will drop to $10 per user per month.

Bryan made a couple of really intriguing points about the challenges of serving as a preservation repository for records created by multiple states. First, partners who don't maintain technical infrastructure don't always realize that problems may be lurking within their digital content. Washington recently led a National Digital Information Infrastructure Preservation Program (NDIIPP) grant project that explored whether its Digital Archives infrastructure could support creation of regional digital repository, and the problems that Digital Archives staff encountered when attempting to ingest data submitted by partner states led to the creation of tools that enable partners to verify the integrity of their data and address any hidden problems lurking within their files and accompanying metadata prior to ingest.

Second, the NDIIPP project and the current Washington-Oregon project really underscored the importance of developing common metadata standards. The records created in one state may differ in important ways from similar records created in another state, but describing records similarly lowers system complexity and increases general accessibility. Encoding metadata in XML makes it easier to massage metadata as needed and gives creators the option of supplying more than the required minimum of elements.

I'm going to wrap up this post by sharing a couple of unattributed tidbits:

- One veteran archivist has discovered that the best way to address state agency electronic records issues is to approach the agency's CIO first, then speak with the agency's head, and then talk to the agency's records management officer. In essence, this archivist is focusing first on the person who has the biggest headache and then on the person who is most concerned about saving money -- and thinking in terms of business process, not records management.

- "If you're not at the table, you're going to be on the menu."

Sunday, April 22, 2012

Help the Library of Congress build a Digital Preservation Q&A site

The Library of Congress's National Digital Information Infrastructure Preservation Program (NDIIPP) is creating a Digital Preservation Question and Answer site using Stack Exchange, a social media service that enables communities of people knowledgeable about a specific subject to develop libraries of reference questions and answers pertaining to that subject.

Right now, the Digital Preservation Question and Answer site is still in the initial stages of creation. In order to progress to the next stage, the site needs to accumulate at least 40 community-suggested questions that have received at least 10 positive votes from community members.

I'm a big fan of NDIIPP, and I think that this Q & A site could become a really valuable resource for archivists, librarians, and other cultural heritage professionals interested in preserving digital materials. If you want to help get this site off the ground, simply:

Right now, the Digital Preservation Question and Answer site is still in the initial stages of creation. In order to progress to the next stage, the site needs to accumulate at least 40 community-suggested questions that have received at least 10 positive votes from community members.

I'm a big fan of NDIIPP, and I think that this Q & A site could become a really valuable resource for archivists, librarians, and other cultural heritage professionals interested in preserving digital materials. If you want to help get this site off the ground, simply:

- Visit the Digital Preservation Stack Exchange Q & A site (currently located in Area 51 -- click the link and you'll see what I mean)

- Become a registered user.

- Review the list of proposed questions, identify the five questions that you would most like to see answered in the final version of the site, and vote for them.

- If you think of additional questions, add them to the list of proposed questions.

Thursday, April 19, 2012

Movies in the digital era

We information professionals have long asserted that the transition from paper- and film-based to digital means of recording information will be profoundly destabilizing. However, when one's working life focuses on the quotidian aspects of facilitating, managing, and mitigating the risks associated with this transition, it's easy to lose sight of just how sweeping the changes will be. And that's why Gendy Alimurung's long, thought-provoking article in last week's L.A. Weekly warrants close reading. Alimurung focuses on the film industry's transition to digital filmmaking and, in particular, projection, which is being hastened along by studios enthralled by the cost savings they will achieve once they no longer have to produce and distribute vast quantities of 35 mm prints. However, as Alimurung points out, this transition and the manner in which it is unfolding has profoundly unsettling implications:

- The cost of digital projection equipment is much higher than that of 35 mm film projection equipment, and even with the subsidies provided by the big studios, a lot of independent theaters are going to find the transition to digital projection prohibitively expensive.

- Most of the big production companies are ceasing distribution of all 35 mm prints, including those of older films for which theater-quality digital versions are not available, a move that will likely cause a substantial number of repertory and art house cinemas to shut their doors or to fall back upon screening DVDs or BluRay discs, both of which look dull and flat when projected onto a theater-sized screen.

- Preservation of digital films is substantially more expensive than preservation of 35 mm films, and the speed with which digital cinema formats change makes preservation even more of a challenge than it would be otherwise. Moreover, just as many silent films were destroyed or quietly allowed to disintegrate after the coming of sound, many older 35 mm films may be allowed to die of neglect.

- The nature of filmmaking itself will likely change -- and not always for the better. As one of Alimurung's sources points out, shooting a movie on 35 mm film imposes a certain discipline: one can shoot only ten minutes of 35 mm footage at a time, and goofing around while a 35 mm film camera is rolling costs money. Some directors will no doubt find that the the freedom and flexibility of digital filmmaking enables them to do amazing things, but some novices, in particular, might not develop the focus and restraint needed to make a halfway decent movie.

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Electronic records roundup

In no particular order, some electronic records news that may be of interest:

- The thoughtful and hard-working folks at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History have explained some of the challenges of preserving the state's digital history. (As you'll recall, gubernatorial e-mail management practices recently gave rise to controversy in the Palmetto State.)

- The archivists at Queens University (Canada) are grappling with similar issues.

- David Pogue and CBS Sunday Morning drew attention to "data rot" -- the problems associated with hardware and software obsolescence. (N.B.: Pogue thinks that the word "archivist" contains a

long "i." - If you're interested in the evolution of cybersecurity, be sure to check out the short films that were shown at the annual conferences attended by Bell Labs executives. You'll find them on YouTube courtesy of the AT&T Archives. (And if you're interested in the history of hacking, be sure to check out Ron Rosenbaum's fascinating 1971 article on "phone phreaking," which captured the imagination of a generation of computer enthusiasts -- Steve Jobs among them.)

- A computer science Ph.D. student has found that, less than a year after the revolution in Egypt, approximately 10 percent of the social media posts documenting it have vanished from the live Web. A variety of factors account for this situation. People sometimes post things, regret doing so, and then delete them. Others get tired of maintaining their accounts and delete or deactivate them. Others were almost certainly the target of government repression and either removed content under duress or had content removed without their consent. The student's overarching conclusion: we need to become a lot more proactive about capturing Web content that documents the unfolding of historically significant events. (He'll get no argument from me.)

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Looking for a digital preservation workshop or course?

The Library of Congress's Digital Preservation Outreach and Education (DPOE) initiative has a new online calendar of online and in-person digital preservation courses and workshops offered by American academic institutions and professional associations.

At present, the calendar includes offerings from the following organizations:

Despite our best intentions, efforts to publicize continuing education opportunities are sometimes scattershot or excessively localized. We've needed a calendar of this sort for quite some time, and I'm really glad that DPOE has created it. I plan to consult it frequently and add to it as appropriate. Please do the same.

At present, the calendar includes offerings from the following organizations:

- AIMS Project

- American Library Association

- Amigos

- Library of Congress

- Los Angeles Preservation Network

- Lyrasis

- National Association of Government Archivists and Records Administrators

- North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources

- Northeast Document Conservation Center

- Purdue University Libraries

- Rare Book School

- Society of American Archivists

Despite our best intentions, efforts to publicize continuing education opportunities are sometimes scattershot or excessively localized. We've needed a calendar of this sort for quite some time, and I'm really glad that DPOE has created it. I plan to consult it frequently and add to it as appropriate. Please do the same.

Labels:

archival education,

digital preservation,

e-records

Saturday, May 28, 2011

New NARA trustworthy digital repositories guidance

I've made it back to Albany and am wading through piles of mail and other stuff that either accumulated in my absence or simply wasn't dealt with before I left town. Included in that pile are a few nuggets of information that I wanted to pass on to you, and over the next few days, I'm going to do just that.

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration has just released Establishing Trustworthy Digital Repositories: A Discussion Guide Based on the ISO Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Standard Reference Model. It contains a brief overview of the six core business processes -- ingest, archival storage, data management, administration, preservation planning, and access -- outlined in the OAIS Reference Model and a series of nicely thought-out questions that enable agencies to assess how well their current high-level policies, practices, and procedures support each of the six processes and to identify needed improvements.

As might be expected, this publication is directed at federal agency CIO's, program managers, and records officers. However, anyone charged with developing and implementing policies, procedures, and processes that support the long-term preservation of college/university, local or state government, or corporate digital materials should examine it closely. It's only twelve pages long and refreshingly free of jargon, which means that non-archivists and non-records managers may actually read it, and almost all of the questions it asks are broadly applicable. Strongly recommended.

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration has just released Establishing Trustworthy Digital Repositories: A Discussion Guide Based on the ISO Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Standard Reference Model. It contains a brief overview of the six core business processes -- ingest, archival storage, data management, administration, preservation planning, and access -- outlined in the OAIS Reference Model and a series of nicely thought-out questions that enable agencies to assess how well their current high-level policies, practices, and procedures support each of the six processes and to identify needed improvements.

As might be expected, this publication is directed at federal agency CIO's, program managers, and records officers. However, anyone charged with developing and implementing policies, procedures, and processes that support the long-term preservation of college/university, local or state government, or corporate digital materials should examine it closely. It's only twelve pages long and refreshingly free of jargon, which means that non-archivists and non-records managers may actually read it, and almost all of the questions it asks are broadly applicable. Strongly recommended.

Labels:

digital preservation,

e-records,

federal records

Wednesday, April 20, 2011

Installing Archivematica

Last week, my intrepid colleague Michael and I started playing around with Archivematica, the first open-source, Open Archival Information System Reference Model-compliant digital preservation system that can be installed on a desktop computer; it's fully scalable, so it also works well in a large-scale Linux server environment. Archivematica, which is being developed by Artefactual Systems in collaboration with the UNESCO Memory of the World's Subcommittee on Technology, the City of Vancouver Archives, the University of British Columbia Library, the Rockefeller Archive Center, and several other collaborators, is still in alpha testing mode, but it integrates a lot of open source digital preservation tools, including BagIt, the Metadata Extraction Tool developed by the National Library of New Zealand, and JHOVE and uses PREMIS, METS, Dublin Core, and other widely used metadata standards.

My intrepid colleague Michael and I have wanted to play around with Archivematica for some time, and last week we finally got around to downloading and installing it. The process went a lot more smoothly than we anticipated -- in large part because we read Angela Jordan's candid Practical E-Records post about her experiences and Michael J. Bennett's detailed Archivematica installation instructions as well as some of the instructions provided on the Archivematica site -- but we did hit a few sticking points. I'm sharing what we learned in hopes of helping other archivists who are interested in experimenting with Archivematica.

Archivematica is designed to operate within an Ubuntu Linux environment, but Mac and Windows users can easily install a virtual appliance that makes it possible to set up an Ubuntu environment on their computers. We opted to install Oracle VirtualBox, which is recommended by Archivematica's developers, and we were both really impressed by the clearly written, logically organized, and complete instructions that accompanied the software. I've encountered a lot of bad installation instructions and user manuals, and it's always a pleasant surprise when I run across manuals produced by good, careful technical writers. However, the manual didn't mention one thing that we and Angela Jordan encountered: as you install VirtualBox on a Windows machine, Windows will repeatedly warn you that you are attempting to install non-verified software and ask you whether you're certain you want to do so. Be prepared to click through lots of dire dialog box warnings.

After we set up VirtualBox, we followed Michael Bennett's instructions for installing Xubuntu 10.4. The installation process was simpler than we anticipated -- we basically clicked through a setup wizard -- but we had to stop work for the day a few minutes after the installation was complete.

Installing Archivematica itself was a bit more challenging. It took us a little while to figure out that we really did have to install it via the Web; much to our dismay, copying the files on the Archivematica Launchpad onto a DVD -- something that we had done several days before -- and then installing Archivematica via the DVD simply doesn't work.

Moreover, Michael and I are both completely new to Ubuntu, so we were a bit flummoxed by the Ubuntu Repository Package instructions that appear on the Archivematica site. I did a little Googling and discovered that we had to access Ubuntu's command line interface to install Archivematica and that we could do so via Terminal. We also found Michael Bennett's step-by-step instructions, which highlight some trouble spots, really helpful. However, Bennett's instructions illustrate how to copy the installation commands from the Archivematica Web site and paste them into the Terminal interface, and for some reason we simply couldn't paste the text we copied into Terminal. We were a little pressed for time, so in lieu of troubleshooting our copy/paste problem, we opted to type all of the installation commands into Terminal -- and hit a few trouble spots of our own as a result.

We hesitantly entered the command to add the first Archivematica PPA, and were gratified to discover that it apparently worked: the screen displayed a few lines of text, the word "error" didn't appear anywhere, and we were prompted to enter another command. We ran the second Archivematica PPA command and the trio of archivematica-shotgun commands without incident, but we had real problems running the vmInstaller-environment.sh. After about half a dozen error messages, we figured out what we were doing wrong: our all-too-human minds led us to read "enviroment," the last element in the command, as "environment."

There is only one "n" in "enviroment"!

There is only one "n" in "enviroment"!

Entering the flock (i.e., file lock) call also posed a few problems. Because we were typing, not copying and pasting, the commands, we first had to figure out whether the five asterisks at the start of the call were separated by spaces; they are. Then we had to figure out how to access the end of the flock call, which is hard to see on the Archivematica Web site. Fortunately, M.J. Bennett's instructions revealed that the text was indeed there, and we could view it when we highlighted it.

The highlighted segment of the flock call reads: /sharedDirectory/watchedDirectories/quarantined" Note the presence of the the quotation mark at the end.

The highlighted segment of the flock call reads: /sharedDirectory/watchedDirectories/quarantined" Note the presence of the the quotation mark at the end.

After we rebooted our Ubuntu virtual machine, we were able to access Archivematica without any problems . . . but had to shut it down immediately and make our way to a previously scheduled event.

Michael and I estimated that it took a total of about four hours to install VirtualBox, Xubuntu 10.4, and Archivematica, and I'm pretty sure that the fumbles outlined above and our repeated readings of various installation manuals took up approximately one hour of that time. Moreover, a lot of the Archivematica installation time was taken up by sitting around and waiting for the commands to execute -- be prepared to see many, many lines of text appear in Ubuntu's Terminal -- and we could have done a little light work (e.g., proofreading draft MARC records, completing travel paperwork) while waiting to enter the next command.

I'm out of the office at the moment and Michael's going to have to focus on other projects during the next couple of weeks, but we'll start experimenting with Archivematica as soon as we get the chance. In the coming months, I'll put up at least a couple of posts outlining our findings.

My intrepid colleague Michael and I have wanted to play around with Archivematica for some time, and last week we finally got around to downloading and installing it. The process went a lot more smoothly than we anticipated -- in large part because we read Angela Jordan's candid Practical E-Records post about her experiences and Michael J. Bennett's detailed Archivematica installation instructions as well as some of the instructions provided on the Archivematica site -- but we did hit a few sticking points. I'm sharing what we learned in hopes of helping other archivists who are interested in experimenting with Archivematica.

Archivematica is designed to operate within an Ubuntu Linux environment, but Mac and Windows users can easily install a virtual appliance that makes it possible to set up an Ubuntu environment on their computers. We opted to install Oracle VirtualBox, which is recommended by Archivematica's developers, and we were both really impressed by the clearly written, logically organized, and complete instructions that accompanied the software. I've encountered a lot of bad installation instructions and user manuals, and it's always a pleasant surprise when I run across manuals produced by good, careful technical writers. However, the manual didn't mention one thing that we and Angela Jordan encountered: as you install VirtualBox on a Windows machine, Windows will repeatedly warn you that you are attempting to install non-verified software and ask you whether you're certain you want to do so. Be prepared to click through lots of dire dialog box warnings.

After we set up VirtualBox, we followed Michael Bennett's instructions for installing Xubuntu 10.4. The installation process was simpler than we anticipated -- we basically clicked through a setup wizard -- but we had to stop work for the day a few minutes after the installation was complete.

Installing Archivematica itself was a bit more challenging. It took us a little while to figure out that we really did have to install it via the Web; much to our dismay, copying the files on the Archivematica Launchpad onto a DVD -- something that we had done several days before -- and then installing Archivematica via the DVD simply doesn't work.

Moreover, Michael and I are both completely new to Ubuntu, so we were a bit flummoxed by the Ubuntu Repository Package instructions that appear on the Archivematica site. I did a little Googling and discovered that we had to access Ubuntu's command line interface to install Archivematica and that we could do so via Terminal. We also found Michael Bennett's step-by-step instructions, which highlight some trouble spots, really helpful. However, Bennett's instructions illustrate how to copy the installation commands from the Archivematica Web site and paste them into the Terminal interface, and for some reason we simply couldn't paste the text we copied into Terminal. We were a little pressed for time, so in lieu of troubleshooting our copy/paste problem, we opted to type all of the installation commands into Terminal -- and hit a few trouble spots of our own as a result.